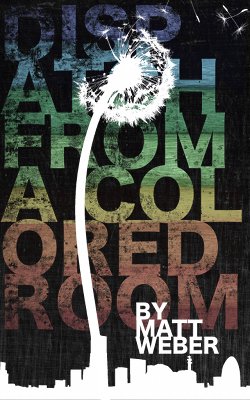

I wrote this a month or so ago for inclusion in THE DANDELION KNIGHT or a related piece of work. It worked better than I expected, even as a self-contained little scene, and it reveals a couple of new wrinkles in an already pretty wrinkly setting. So I like it.

—

There is so much to say, but in some sense the first thing that happened is this:

They came in the night to the back door of a modest brick tenement, two floors of residences above two of business, and discreetly rang the little bell that hung nailed into the moulding. The door opened immediately; a man had been waiting in the stairwell. His face was black-bearded and thin, his skin dark and fine but losing its firmness, as though in greeting the men who had knocked he had stepped over the jamb separating youth from middle age. In his arms was the baby.

The men who had knocked were three, of unremarkable appearance, dressed for business in drab suits and cravats. The one on the left, who was big and young with a thick shock of dark hair, had a handgun at his side and a great padded basket strapped across his shoulders. The one on the right, who was spare and pale and older, though his hair was no less thick, carried a hard-shelled briefcase. The one in front was short and compact, and his scalp was covered only by the close-cropped stubble of a receding hairline. He had a kind face, and the man with the baby recoiled inwardly at that. It was the middle of the night in the month of Greslose, and the man with the baby felt his nose hairs freeze a moment with each breath he took; he did not fail to notice that the three men who had knocked wore no overcoats.

“Thank you for waiting,” said the kind-faced man. “I’m afraid there are legalities. We can go inside if it’s more comfortable for you, but some people prefer not to have us in their homes. We understand, of course.”

“I’ll ask you to exercise your understanding, then,” said the man with the baby.

“Very well,” said the kind-faced man. “M. Imendoint, the identification kit, please.”

The spare older man smoothly cradled the suitcase in his left arm and opened it with his right, revealing a multi-compartment interior padded with blue quilted canvas. In the central compartment was a flat, round-cornered box of off-white bioplass, considerably scuffed and scratched and pen-marked, with a serial number embossed on the lid. Embedded in the front were two vertical strips, each with a little lens, a clean white pad, and a little well with a needle sticking straight out from the center. On the top edge of the box were three more needles. The kind-faced man removed the box from the suitcase; the man with the baby reached for it, but the kind-faced man shook his head. “I hold it,” he said. “You verify your own identity, then the baby’s. You know what to do?” The man with the baby nodded and stared into one of the lenses, which responded with a brief flash of red; then he licked his finger, pressed it to the clean white pad, and pricked it with the needle. The pad slowly turned blue.

“It’s you,” the kind-faced man said, and the man with the baby glared at him. Then he looked at the baby, who was still asleep even in the nose-hair-freezing cold. “I’m afraid there’s no getting around the finger-prick,” said the kind-faced man. “It’s cruel, but not so cruel as it would be for us to take the wrong child.” To some stirring of the man with the baby’s expression, he added, “Have no fear, we’ll comfort her. And M. Drontois can take care of the child’s identity if you prefer.”

The man with the baby shot him a look of scorn and took the child’s head in his hands gently but surely, positioned her in front of the other lens, then moved a hand up to pry her eye open. The baby began to cry a fraction of a second after the lens had recorded her retina; the man who held her took a hand and moved it up to her open mouth, provoking a fresh howl, and pressed it to the pad and then the needle, provoking another. The streets were sheathed with just enough snow to damp what would otherwise have been a fine reverberation from the stone and asphalt. The man fixed the baby’s swaddle, then put her on his shoulder and began to rock and shush her; she cried as though the world were ending.

“And that’s her,” said the kind-faced man, indicating the second pad, which had turned a fainter but no less distinct blue. “Give her to M. Drontois, please; the paperwork requires the clearest handwriting possible.” The spare older man drew a clipboard from a pocket in the quilted suitcase and offered it to the kind-faced man; the big young man, Drontois, held out the basket.

The man with the baby ignored Drontois and looked at the clipboard as though it were an artifact of a long-defunct civilization. The kind-faced man allowed him a moment before speaking. “Pardon my bluntness, sir, but this moment was coming, before or after you completed the paperwork. I have done this once or twice, as I’m sure you know, and I assure you that holding on to her longer would make the culmination of this encounter no easier. Whereas, if we had to come back to your house tomorrow to verify some portion of these forms, because the handwriting was—”

“I’m not trying to make anything easier,” said the man with the baby. She had not quieted yet, but her sobs had become more strident than desperate, protests rather than lamentations. The man with the baby wondered whether the kind-faced man or his associates had spent enough time with children to understand the difference between their different cries. Probably, he was forced to admit, they had; and that, of course, was worse than if they had not. He brought the squalling child’s head up to his own, hoping he might be able to look into her eyes in a divinely granted moment of peace; but they were screwed shut, the skinny strong back kipping with undirected fury. A tiny taloned hand caught him across the cheekbone with a scratch whose power somehow, after raising two other children and, for just a few days, this one, surprised him. She was too young for tears. He kissed her forehead, which only enraged her further, and drew in the scent of her skin and of the down of her scalp with a deep but quiet breath. Then he put her in the big man’s basket.

The big man covered her with another blanket, thicker than the one the bearded man (for he no longer had a baby) had swaddled her with. The kind-faced man extended the clipboard.

She had quieted by the time the bearded man was done. He looked at her still form, the arms barely thicker than his thumbs and so short they would barely touch the top of her head, the thin chest working like a bellows. He took a step toward the big man, Drontois, and crouched down to put his head at the baby’s level; in his visual periphery he saw Drontois stiffen and nearly recoil at the unexpected motion, but the three men allowed him this last indulgence. He kissed his the tip of his forefinger, pressed it to the infant’s forehead, then lay it in her palm; her hand closed around it. He waggled the finger to move the arm. Still she did not wake. He reclaimed his finger and stood.

“Some families find it comforting to hear of the good work their children will do for Altronne,” said the kind-faced man.

A thing came to the bearded man’s eyes that either answered or silenced the kind-faced man. “As you wish,” he said, just as though the bearded man had spoken. He began to turn to go, but something made him meet the bearded man’s eyes one more time. “This has happened to all of us,” he said. “M. Drontois’ first and only child—but he is young. My second; we had another after. M. Imendoint lost a child and a grandchild.”

The bearded man received this news mutely.

“We have observed you carefully here,” said the kind-faced man. “We will enter your name into the list. The list contains only men and women who love their lost children despite knowing what they are. The directors review the list and ask selected citizens to do the work we do.” He paused here, to let the bearded man react if he would. “If you are selected, and you accept, you may see her.”

The eye’s colored iris is as opaque as a signal flag, which is what it is, an adaptation to life in a complex society where gaze is as much communication as it is interrogation. The pupil is merely a hole; the lens behind it exists to focus light as it penetrates the eye, and the retina exists to absorb that light and speak of its nature to the brain. In short, there is no meaningful physiological sense in which light can be said to emanate from the eye. But there are more meaningful senses than the physiological, and anyone staring at his face would have sworn up and down that the flare in the bearded man’s eyes was bright enough to leave the three men flash-blind.

“Why tell me?” he asked.

“So you can contemplate your answer,” the kind-faced man said. “They are not human, Jon. You will see, if you say yes.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“You say that now.”

“Does it matter?” asked the bearded man.

“I would hardly have mentioned it if it did not.”

“Do you wish you had said no?”

“I cannot answer that.”

The bearded man nodded. The tears were streaming freely now, stiffening in tracks in the black beard. “You can go now.” Before I rip her free of that basket and run Imen knows where, he thought but did not say.

The three men turned their backs without another word, and the bearded man shut the door to the back stairs, ringing the little bell with the impact. He gave a second’s sober thought to crumpling on the very bottom stair and letting the sobs shatter him; but he rejected that. He would undress and meet his wife in bed. If he wept then, he would weep. The children were asleep—and if they did hear him, perhaps it was all to the good. Better for them to learn to cry before their loved ones, was it not, where dignity could be recovered, rather than in cold abjection, on the mercy of some thoroughfare’s transient disuse? Better, was it not, to memorialize their sister with grief, rather than lose all memory of her in a child’s trust that what adults decided must be for the best?

But his wife was asleep, as it eventuated, and neither she nor his children were awakened by his tears—nor by the soft chant, through them, of the name he had never told anyone, the name no one but him would ever know to call that nameless, absent girl.

No one but him, that is, and me.